Work has been a standard feature of human life as long as we humans have existed.

It puts food on our tables, it keeps order in our societies (well at least some order). It builds civilizations and sometimes it dismantles them. As a child, I had only a vague idea of work. It was the place my father disappeared to each day, and it was what he did in his study at home after dinner most nights. He was an architect and was doing the same type of work as his father, his grandfather, and even his great grandfather, who were also all architects.

My father liked to work. He was always busy. As a child his family called him “termite” as he was always chewing on a new challenge. Although he was motivated not to be poor, he wasn’t fixated on being rich. After all, architects (for the most part) are driven more by passion and inspiration than by money. My father was very athletic; in school he was a gymnast, a diver, a tumbler, and a trampolinist. Even before he got out of college, he began a career as a professional juggler in Boston. At the very end of World War 2 he was drafted into the Army, and when they found out he was an accomplished juggler, he was put into Special Services basically to entertain the troops. Yes, he spent some time learning how to man a 105 mm howitzer, but for the most part he had his days to himself and could train full time at the base gym. He told me later that it was one of the happiest times of his life, working on his skills and teaming up with some of his fellow Special Services buddies. He thought life was just grand. He had a purpose and now an opportunity to practice towards that purpose full time. My mother remembered seeing posters of my father performing his craft when she was in college and then they met and later married. Her father was a judge and old school. He didn’t think his daughter should marry a juggler, so my father took up the family profession and made architecture his permanent career.

There was plenty of evidence around from his acrobatic and juggling days. As small children, we performed all kinds of acrobatics with him at the beach. We had an in-ground trampoline in the back yard where Dad performed ariel feats of grace, and we learned to do flips, pikes, and even back flips. We never got close to his level but then again, we were just kids. Dad played close to a dozen musical instruments, ranging from piano and tenor banjo (on which he was extremely proficient) to trumpet, French horn, guitar, and many more on a casual level. He used to say he really wasn’t a natural musician because he didn’t have my mother’s ear for pitch; he had to work at music harder than she did, but he became an accomplished musician because of all that practice. He worked hard at it but learned to love the process.

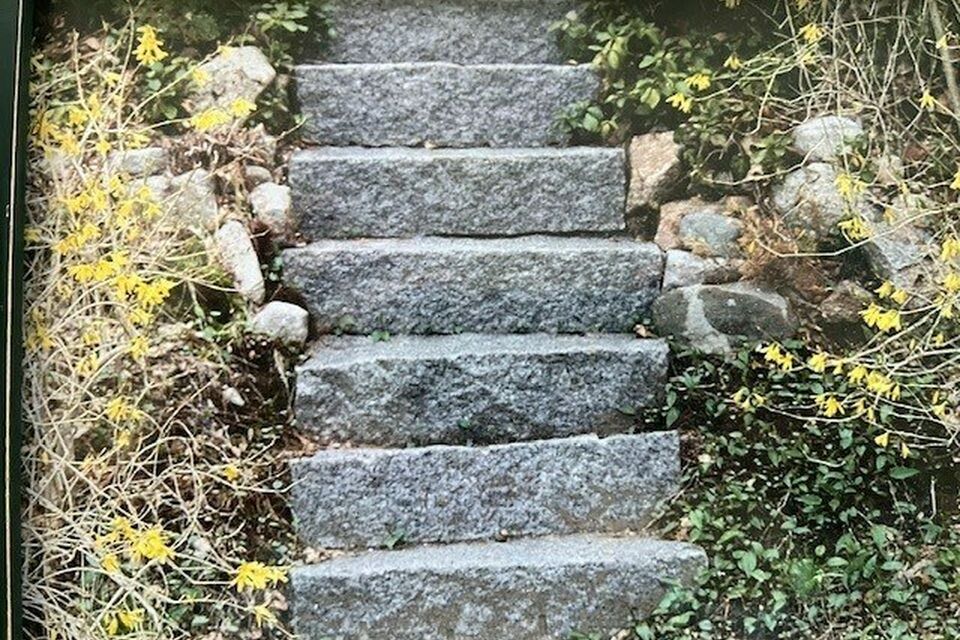

When I was 17, he asked me for some help building stone steps into a bank in the back yard. They were formed of heavy granite blocks, each weighing some 150 pounds. I had two things going against me, the weight of the blocks and the fact that as kids, who of us enjoys family projects? I was a bit impatient; he wanted to study things, plan things, and proceed slowly. I wanted to get the job done so I could go back to whatever adolescent entertainment I would have preferred to a “help Dad” project (you know the feeling). Apparently, I said to my father, “Stand back, Dad, I’ve got this” and he did, and I did. I wrestled those blocks into place, taking care that they were plumb, level, and square in a bed of well compacted, processed stone dust. Later, he told me he couldn’t believe that 1) I knew what to do and 2) I did it so diligently. For my father, it was a realization that maybe I could amount to something. For me, it was an introduction to the pride of a job well done. 30 years later, long after they had sold that house, I went back to see those steps. Here is what they looked like 30 years later…. plumb, level, and square. I didn’t own the property, but I owned the steps!

No task lasts forever, so there is always an end. The means to that end might involve patience, motivation, self-assurance, and focus. The task at hand doesn’t have to be a punishment; it’s just another task at hand so why not relish the challenge? Why not practice the elements of success while solving a need or a problem or developing a new set of skills? If we’re lucky, we are getting paid for it, like my dad practicing juggling in the Army getting three hot meals, a cot, and even a small paycheck doing what he was learning to love. He made the Army one of the happiest times of his life!

I can’t afford to wait for things to come along to fall in love with. I learn to love the task at hand. I do that by thinking what that task will lead to, in the big picture. I take that task from menial to monumental; I make that task as important as it can be. I am not thinking “I hope this will happen”, I am visualizing myself already well done the road to success. My Dad told me a story of the building of St Paul’s Cathedral in London in the late 1600’s. The architect, Sir Christopher Wren was inspecting the progress of construction, and he came upon a mason. He asked the man what he was doing, and the man replied that he was laying one block of granite on top of the next block and that he had many more to go. Around the corner, Sir Chrstopher found a second mason doing the exact same job and when he asked the same question, he got back a different answer. The second mason said, “I am building St. Paul’s Cathedral!’ Which mason would you like in your job, and which mason would you trade places with?

A friend of ours in Florida has an older boat with a generator aboard that came with the boat that he has owned for many years. The generator started but then stalled out after a few seconds. He had brought in the usual qualified marine experts to diagnose the problem and after hours and hours of expensive diagnosis, no one was able to come up with an answer. We called a yacht broker friend in desperation, with visions of a new $12,000 generator entering the picture (this one is almost 40 years old). Our broker friend suggested a one-man mechanic, who then suggested another one-man mechanic who lived conveniently nearby. After a couple of hours on the job, he solved the case for a small fee. Unlike the “experts”, he started patiently to find the source of the problem, that everyone else had missed. It was a fuel supply issue that no one else could find. He didn’t take “no” for an answer. It summoned up the old saying, “Those who say it can’t be done should get out of the way of those who are ready to do it.”

“People who say it cannot be done, should not interrupt those who are doing it” -Bernard Shaw

If we want to succeed, we have to stop thinking about Wednesday as “hump day”. Wednesday is just the gateway to the rest of the week! Instead, we have to start thinking about the mason who was “building St. Paul’s Cathedral”. We need to embrace life and the opportunities that are dressed up as challenges. For a good short read, pick up a copy of Be Useful: Seven Tools for Life by Arnold Schwarzenegger. The man is on his 4th successful career (Bodybuilder, Actor, Politician, Philanthropist/ Social Change Agent). He gives some great advice. He takes charge of his attitude.

Here is my advice. Don’t fixate on what you don’t have, dare to dream of what you want and act on those dreams with focus, with patience and tenacity. You are in charge of your attitude, no one else is. Live your life and cherish your opportunities! Be grateful for what you have and go after that dream with excitement.